These days, sending a child away to a state university can cost over $100,000, and at selective private colleges, it’s easy to spend $300,000 on four years of education … and if you’ve got two or three kids to put through college, well, you may end up spending more to educate your children than you paid for your home. The numbers are staggering, and when you consider that the cost of education has risen at the same time as the cost for healthcare and housing, frankly, it’s all a little overwhelming.

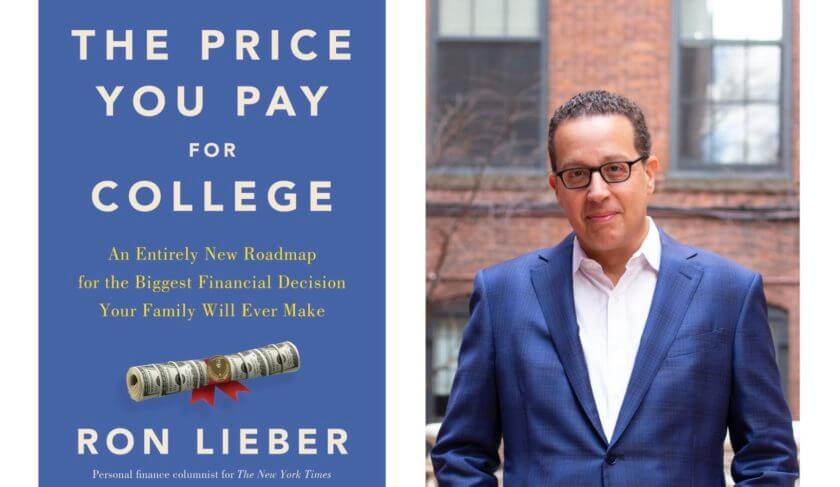

These are a few of the hard truths shared in author Ron Lieber’s incredible new book: The Price You Pay For College: An Entirely New Road Map for the Biggest Financial Decision Your Family Will Ever Make. The book just came out at the end of January, and it pulls the curtain back on why college really costs so much, and it explains how the financial aid system for colleges and universities got so complicated. Ron breaks down what’s really worth paying extra for, and what’s not, and walks us through the best savings strategies.

Ron is the “Your Money” columnist for the New York Times, the author of several books and a three-time winner of the Gerald Loeb award, business journalism’s highest honor.

Listen in as Ron discusses what inspired him to write the book, and why it’s a must-read for families sending a child to college these days. Jean references one of her favorite passages:

“The most daunting part of the process is this: There is often no way to know what you’ll actually pay until the very end of a tumultuous application process. Only after acceptances are out do the schools offer unpublished discounts and negotiate with families who file appeals, one by one, over the final bill. It all happens in secret… Getting to the final, cumulative price tag requires a long journey, and the maps available to guide families are pretty crude.”

And Ron tells us how it all got so complicated — and so expensive. Why does it feel increasingly like colleges can make things as complicated as they want, set prices wherever they want, and we have no choice but to play along? (Because applying to college should be exciting — not something that makes us feel powerless!)

Ron breaks down the concepts of “value” and “worth” as they relate to college, and how to know if you’re getting a deal. He also talks about merit aid, which he describes in his book as “a complicated and often opaque form of tuition-discounting.” But it’s something most colleges do these days. He helps us understand it.

We also discuss the ways colleges “discount” tuition with various forms of financial aid these days, and why some private colleges discount their list prices by as much as 50% for most applicants. Ron also discusses the most important takeaways from his chapters on saving for college, the professional advice you should seek, and how much you should borrow when the time comes … Lastly, he takes a stab at one of our Mailbag questions from a listener who is considering subletting her apartment to pay for her son’s college education.

Kathryn and Jean tackle the rest of the Mailbag, with questions on how to establish Roth IRAs for young people in college, and how to prioritize paying down student loans vs. saving for retirement. Then, in Thrive, Jean dives into the 5 financial moves you need to make now to get your high school senior ready for college next year.

This podcast is proudly supported by Edelman Financial Engines. Let our modern wealth management advice raise your financial potential. Get the full story at EdelmanFinancialEngines.com. Sponsored by Edelman Financial Engines – Modern wealth planning. All advisory services offered through Financial Engines Advisors L.L.C. (FEA), a federally registered investment advisor. Results are not guaranteed. AM1969416

Transcript

Ron Lieber: (00:01)

It’s important for people to understand that what we have here is a thriving market that is extremely competitive. And we have a customer base that is increasingly part of an economy where there is more and more income inequality. So while there are people who have the ability to pay, and maybe even a few more of them than there used to be on sort of a per capita basis, many of the people with the ability to pay, or close to it, are increasingly questioning whether they ought to have the willingness. They’re asking a value question.

Jean Chatzky: (00:42)

HerMoney is supported by Fidelity Investments. Whether you want to get your savings back on track or you’re working toward a brand new goal, Fidelity has tips and tools to help you meet your short and long-term savings goals. Please visit Fidelity.com/HerMoney to learn more.

Jean Chatzky: (00:58)

Hey everybody. I’m Jean Chatzky. Thank you so much for joining us today on HerMoney. These days, sending a child away to a state university can cost over a hundred thousand dollars. And at selective private colleges, it’s easy to spend three times that on four years of education. And if you’ve got two or three kids to put through college, well, you may end up spending more to educate your children than you paid for your home. Just think about that for a second. The numbers are staggering. And when you consider that the cost of education has risen at the same rate as the cost of healthcare and housing and the need to fund our own retirement, frankly, it’s all a little overwhelming. These are a few of the hard truths shared in author, Ron, Lieber’s incredible new book, “The Price You Pay For College: An Entirely New Road Map for the Biggest Financial Decision Your Family Will Ever Make.” The book came out just at the end of January. It debuts this week as number four on the New York times bestseller list. And it pulls the curtain back on why college really costs so much. It explains how the financial aid system got so complicated. Ron breaks down what’s really worth paying for, and what’s not, and walks us through the best saving strategies. And you all know Ron. He’s been with us before. He is the Your Money columnist for the New York times, the author of several books, a three-time winner of the Gerald Loeb award, which is for those of you who are not business journalists, it’s like our Oscars. It is the highest honor. And he is joining us today from his home in Brooklyn, Ron, hi. Thank you much for coming on.

Ron Lieber: (03:00)

It is my pleasure and my honor to be back. Thank you, Jean.

Jean Chatzky: (03:03)

Oh, of course. So I want to just start by asking you what inspired you to write this book. But before you answer that question, let me just tee it up with a passage that I found in your book that I loved and that I think really sums up why this book is so very needed for all families right now. You write, “the most daunting part of the process is this. There is often no way to know what you’ll actually pay until the very end of a tumultuous application process. Only after acceptances are out do the schools offer unpublished discounts and negotiate with families who file appeals one by one over the final bill. It all happens in secret. Getting to the final cumulative price tag requires a long journey and the maps available to guide families are pretty crude.” When did you figure out that this was the truth?

Ron Lieber: (04:07)

It took me decades. And it took decades for the system to evolve into the bonkersdome that you just described, right? I mean, it started for me when I was in high school because my family did not have enough money for me to go to the schools that I wanted to attend. And so we learned back in the late eighties about the old fashioned, need-based financial aid system. But while nobody was paying attention over the course of the next handful of decades, this second track, that became known as merit aid, emerged without anybody really paying attention. At the same time, the list prices were going to the moon. You know, they hit those $300,000 marks at the privates and $100,000 at the publics. And here’s what was happening, right? Professionally, and you know this story too, we spent a lot of time, 10 or 15 years ago, spilling ink and talking on TV about how to save for college and these new 529 plans. And they weren’t so good. And the fees were too high. And then they got a lot better. We spent a lot of ink and a lot of time on TV talking in 2010 about the last recession and all of the people who were washing out of these schools with too much student loan debt, right? So we talked about that problem, how to pay for college. But what I missed was that the thing that people seem to be struggling with the most was not how to save, not how to pay. It was what to pay for college. They were asking value questions. And then so many of them were ending up at the end of the process, literally crying into my inbox or my cell phone in late April every year, if they knew how to get to me, because these otherwise smart and sophisticated people had no idea how the system actually works. Some of them didn’t even know what merit aid was until after their kids were offered it unbidden. And I thought, wow, I have really missed it. I have messed it up. The system is messed up and I need to do something about it.

Jean Chatzky: (06:03)

Look, I don’t think you should be that hard on yourself, quite frankly. I mean, you have lifted the veil on a lot of mysteries when it comes to college financing over the years. Your column is a must read. And your work on public service loan forgiveness alone has been just remarkable. So I think you should give yourself a break. But how did it get so complicated and how did it get so expensive? It feels like colleges can make things as complicated as they want, that they can set prices wherever they want, and that parents and students have no choice, but to go along,

Ron Lieber: (06:46)

Well, there are two questions in there, right? How did it get so expensive? And how did it get so complicated? So let’s tackle the expense first, cause that’s a slightly easier one to answer. Think about the publics and think about the privates. The publics have problems because the state legislatures do not give them as much money as they used to. And when that happens, the easiest thing to do is to raise tuition on the in-state families, and then also to try to attract more out-of-state families, paying inflated rates for the same education. So that’s what happens at the publics. Now what’s happening at the privates, and to the lesser extent the public’s too. You know, what we need to be cognizant of about these institutions is that they are expensive to run. There are a lot of parallels to the healthcare system, just in terms of the opaqueness and the expense, and the fact that everything is rising at three times the rate of inflation or whatever. But the other thing that’s similar is that there are highly trained people who work in these institutions and that’s actually what we want, right? We want our physicians and our nurses and our hospital administrators to be well-trained. We want the professors and the people who work in the counseling center and the deans to be good at what they do and to be experienced. But those people expect to be compensated at a higher than average rate. And in order to make sure that the schools are meeting our demands as parents, costs just have to go up, right? And I don’t think we’d like it if 20 or 30 or 40% of the costs were stripped away. So that’s the expense side of it. You know, the complexity side of it. I mean, how long do we want to go on for? I mean, should we talk about merit aid and where that came from?

Jean Chatzky: (08:27)

Yeah. I mean, let’s talk about what people actually pay for college. When we look at prices these days, there is the sticker price, right? There is the amount of financial aid, which typically brings you down to the net price. And there are different forms of financial aid. There is need aid and there’s merit aid. So break it down and explain why merit aid is really the complicating factor here.

Ron Lieber: (09:04)

Sure. Well, I guess to take a step back, it’s important for people to understand that what we have here is a thriving market that is extremely competitive. And we have a customer base that is increasingly part of an economy where there is more and more income inequality. So while there are people who have the ability to pay, and maybe even a few more of them than there used to be on sort of a per capita basis, many of the people with the ability to pay or close to it are increasingly questioning whether they ought to have the willingness. They’re asking a value question.

Jean Chatzky: (09:46)

Yup.

Ron Lieber: (09:46)

And how are the schools answer it? Well, you know, if you look at private institutions, the average discount rate at private institutions is more than 50% at this point, right? So many of us are used to anchoring ourselves in the top 100 most selective institutions. But there are hundreds more behind them that are all discounting at sort of rampant rates. So what are we talking about when we talk about discounting? We can understand if there’s a gap between ability to pay and willingness to pay then naturally discounting it’s gonna result, right? But how does that actually work and what does that mean? So the old fashioned need-based system, the one that I went through as a teenager, still exists and it hums along and it’s reasonably predictable, because these schools have to produce this thing called a net price calculator, where you put your information in and it needs to be pretty accurate. But the other thing that started happening in the nineties is this merit aid system came into existence. It’s a lot like the academic scholarships of old, but the colleges were essentially using them as competitive weapons. I mean, think about it in terms of tiers in the marketplace. If the third tier institution in a particular state decides to go after the second tier institution, and wants to be a second tier institution itself, one way you can do that is by printing a bunch of $10,000 coupons and handing them out to teenagers, right? And then you get yourself better students and hopefully you rise up in the US News rankings and more people are willing to come to your school next year without the discount. So it makes a certain amount of sense, unless there’s a competitive response, right? And so if that goes on for a couple of decades, which it has, pretty soon you get to the point where we are now, where all but the let’s call it 40 or 50 most selective institutions in the country, both public and private, are doing these discounts on the basis of merit, right? So some of them, the most selective ones still actually run real merit aid programs where only 10, 20, 30% of the people who don’t have any need-based financial aid are getting these awards. But farther down the food chain, there’s been so much that everybody gets a trophy. But the thing is, people don’t know that. They don’t know how it works. They don’t know what the average amount is. And the schools are using them as sort of marketing tools to make people feel good about themselves. Even though everybody is getting one. So I wish it was simpler than that, but that is about how it has evolved.

Jean Chatzky: (12:13)

So let’s put on our parental hat for just a second. For the last, I don’t know, 10 years now, when we talk on this show about how to approach the process of applying to college, particularly if you are worried about paying for it, and pretty much everybody is, my advice has been, cast a pretty wide net. I mean, you want to be applying to schools that really want to have your child. Is that what we’re talking about here? Where you are throwing your hat into a ring where you’re likely to get some merit aid. And is there a way for parents to go about this process in an organized fashion so that they don’t drive themselves bonkers?

Ron Lieber: (13:01)

Yeah. So you have it exactly right. And then there are some asterisks that have resulted from the pandemic, which we can talk about in a second. But the basic principle is correct, right? Cast a wide net, apply to more schools, and make sure that at least three or four of them are schools that are likely to want your child enough to throw money at them, assuming price is not no object. So how do you figure that out without going crazy? The schools do not make it easy. So there’s this thing out there in the world called the common data set, which just about every school produces. And what the common data set tells you, in so many words, and I walk people through in the book, how to find line H2A of the common data set. What H2A is in normal people’s English is H2A is where they tell you how much money and to what percentage of people they have to give away to families who don’t actually have any need-based aid. So let’s say you’re a family that earns $200,000 – $250,000 a year. You’re applying to a private college. Maybe you don’t have any need-based data at all. Or any eligibility, right? But you can’t go around writing $75,000 checks each year. That’s out of the question. So you’re looking for merit aid. Those schools know it, and they offer it in ever increasing amounts. So the common data set is where you find that. And elsewhere on the common data set you can figure out, okay, is my kid in the top 25% of the entering class, at least as far as last year statistics were concerned. So you can find test scores and you can find GPA and you can begin to get a sense. All right. Where does my kid stack up? So why is it that complicated, right? Why do you have to go form by form? Well, it’s not in the school’s interest to make this transparent because then people would be more demanding. They would do more negotiating on the backend after they get the offer. You know, an informed consumer in this instance is not necessarily one that helps the school’s bottom line. That’s not always true. So let’s just stipulate that too. Cause different schools at different places in the market handle it differently. Private schools that are really hurting for students, they may just post a grid that explains the whole thing. And it’s GPA over on one axis and test scores on the other. And you see where the two lines cross, and then you know how much of a discount Lake Forest College in Illinois or Wabash College and in Indiana will give you. The University of Alabama is pretty transparent about their numbers for out-of-state students. But at more institutions than not, you’re going to have to guess. And sometimes the net price calculator will give you some merit aid estimates. And there are few schools like the College of Wooster or Whitman College in Washington that will allow you to call in to get an estimate. But it’s kind of a scramble. It’s so much of a scramble that all of these for-profit entities have started up in the last year or two, like EdMit and Tuition Fit and Merit More, to kind of coover up all of this data and spit it all back at you in an organized fashion, so that you don’t have to do all of this.

Jean Chatzky: (16:15)

Are there any trends when it comes to smaller schools versus larger universities and how they tend to shake out?

Ron Lieber: (16:22)

No, it really depends on where they are in the marketplace. And this is another thing that isn’t easy to figure out. You’re trying to sort out for yourself, okay, well this school that I think I’m interested in, who do they compete with, right? Because if I want to have some bargaining leverage at the end, it’ll be nice to have offers from schools that the school that I’ve identified as my number one target would be upset to lose me too, right? So you don’t have any leverage, or you don’t have as much leverage, unless you have other offers where the net price is going to be lower, because otherwise they’re not going to have a conversation with you or the conversation will be shorter, right? So how do you even begin to figure that out? I mean, you can sort of Intuit it, right? If you’re taking a college tour in Ohio, you have a general sense that Kenyon doesn’t really want to lose students to Oberlin and Denison would prefer to buy Kenyon students away to improve the quality of the data in the freshmen class at Denison, right? But it’s hard to know for sure. Fisk, the Fisk College Guides, offer some information on overlapping and competing schools, but there isn’ really a clear way to figure it out. And it’s just one of many things that sort of baffling and confounding about the system. A lot of us are just flying blind. And when I started taking a closer look at it, I just could not believe how complicated it had gotten and I wanted to help.

Jean Chatzky: (17:52)

Absolutely. And the book completely fulfills that promise. But I want to throw another factor into the mix. An emotional 18 year old, who has had his or her heart set on X, Y, and Z school since you took him to a football game when they were 10 years old. Think about that for a second, because I also want to remind everyone that HerMoney is proudly sponsored by Fidelity Investments. When the market is uncertain, it’s more important than ever to have a plan for your savings. And that’s where Fidelity comes in. They will work with you to create a savings and investment strategy and help you fine tune it whenever life changes. Plus they’ve got tips and online tools like their Planning and Guidance Center. They also, apropos of this conversation, have some great college planning tools and all of these things can help you meet your short and long-term goals. So visit Fidelity.com/HerMoney to learn more.

Jean Chatzky: (18:54)

I’m speaking with Ron Lieber, the author of “The Price You Pay For College: An Entirely New Road Map for the Biggest Financial Decision Your Family Will Ever Make.” So last year I produced a video for one of our clients where I talked to some college students and parents about the decisions about where to go. And the applications had been in. The acceptances had rolled in. They knew what the price tag was going to look like. And I ran across kids who were going to more expensive schools than their parents really wanted to pay for. Were they better schools? I don’t know. Would they get a better education there? I don’t know. But there’s a lot of emotion that starts to play into this. So how do we talk to our kids about the fact that value has to be a factor in this conversation? And how do we decide what is worth paying for?

Ron Lieber: (19:54)

Well, the thing about the emotional component of this, and it is not small, it’s tempting to kind of brace ourselves for teenage emotions, but those are sort of a given to me and kind of a baseline. The thing that I’m trying to train people to consider, or retrain them to consider, is to anticipate their own parental emotions about the situation, right? And there are at least three that I’ve identified that can get in the way of clear-headed decision-making and may result in the kinds of choices that you just described, right? There is fear. Fear that our kid will go tumbling down the social class ladder that we have spent years or decades or generations trying to climb, if and only if we make the wrong choice. And often the wrong choice is one that costs less. Or that’s the one we’re worried will be the wrong choice. Because if it costs more, it must be better, right? Then there’s guilt. Guilt that we do not earn enough. Guilt that we have not saved enough. Guilt that we are not doing what our parents did for us. Guilt that if our parents did nothing for us, that we are not doing everything for our kids. The guilt that our kids may try to heap on us for all of these reasons or for all sorts of other ones, right? And then there’s snobbery and elitism which, you know, come April 30th at 10:30 at night, and you haven’t yet made the decision for May 1st. It’s so easy to default to the name that everybody seems to have heard of or the place that the other kids in town went to last year, and not kind of stand by your convictions, because you’re just worried about what other people will think, even if you’ve got your own inner snob or inner elitist under control. So I’m trying to encourage people to make more emotionally intelligent decisions. And so once you do that, then you’re in value land as you put it, right? And so there are a couple of things there. First of all, I think before you even start, you need to have a better sense for yourself of what you’re actually shopping for in the first place. And I’m surprised the extent to which people don’t do this. You know, I ask people repeatedly, for years, what is college to you anyway? And they sort of looked at me funny, but then they begin to spit out answers. And, you know, I hear three things over and over. College is about the education. It’s about the kinship, right? The people you meet along the way, including the mentors, the professors. And it’s also about the credential, which can be, you know, sort of a baseline degree that gets you into a recession-proof or near recession-proof profession like nursing or accounting, or gets you into medical school. Or it can be the kind of brass ring gold-plated degree that will open doors or could open doors, to your child that you would not be able to open for them via your own connections or privilege, right? You know, that’s like really leaping for the most selective schools with the best connection. So it starts with being honest with yourself about what you’re shopping for, right? Cause it’s hard to define value if you don’t know what the definition of success is.

Jean Chatzky: (23:06)

Right.

Ron Lieber: (23:07)

So you define the definition of success and then you go out and you ask a lot of really hard questions of the schools. About what is really happening with salaries when people graduate by major, and that data is now available via the federal college scorecard. You’re asking questions about the odds of getting into grad school. It turns out the federal government releases all sorts of really granular data on where the PhD marine biologists actually come from. Like where were they educated as undergrads. If you’ve got a 17 year old who wants nothing more than to do science on the ocean, you can answer a lot of questions for yourself about whether it’s worth an extra $200,000 to send them to Occidental instead of UCLA. These are things that we can know. You can ask questions about size. You can ask questions about who’s actually doing the teaching. You can ask questions about the most important unit of friendship at any given school, which is the first year roommate, right? Does the school assign roommates? Does it allow you to pick roommates? What does that say about how a school values diversity? You can ask about young female scientists and just how much more likely they may be to persist in a biology or a comp-sci major at a women’s college than they might be at a large flagship state university where the intro level courses are filled with cutthroat teenagers, right? These are things we can know. And in every chapter on each of those questions, I include a list of, you know, five, 10, 15 super pointed questions that we should put to these institutions. I’m trying to encourage people to feel more entitled to more information and better answers. At $300,000 a year, we should not feel like supplicants in this process.

Jean Chatzky: (24:50)

Totally agree. You mentioned the top 50 schools and how they don’t discount. How do you know if it’s worth it if your child gets into one of those? How do you make that decision, particularly if they don’t know what they want to do. I mean, I’m thinking of my own parents who absolutely had to struggle to put me and my two brothers through college. They subdivided the property that our house sat on in West Virginia and sold half of it in order to pay my college tuition at Penn, because they had decided that it was worth it. But how do you make that decision?

Ron Lieber: (25:40)

It’s extremely difficult. So, you know, if we want to imagine young Jean, at 17, it’s possible that young Jean wanted nothing more than to go work at Morgan Stanley in the analyst program. And she knew that at 17 and she wanted to go and work for a gold-plated Wall Street firm when she was done with her four years at Penn. And if that was her goal, then Penn was going to be worth it no matter what. Why? Because the people who run Wall Street firms are a bunch of elitists snobs. And like it or not, for the best analyst programs at these firms, they only hire from a large handful of schools. And Penn is pretty near the top of that list, right? So, for young Jean inspiring investment banking analyst, it would be worth it. If Jean did not know what she wanted to do.

Jean Chatzky: (26:32)

I had no idea. None. I went in. I was going to be a math major. I got a C in calculus and I was all of a sudden an English major, right? Like I, I had no idea.

Ron Lieber: (26:46)

Yeah. So in that instance, if college is mostly an intellectual exercise or if that’s how the student sees it, then the $300,000 school becomes something of a luxury product. And you have to think about how you think about luxury products and luxury brands and what they may be worth to you. And if we sort of put it through the three prisms, here are the questions you have to ask yourself. Is the level of teaching and the level of peer engagement in the classroom, is the learning, going to be all that much better at Penn than it might’ve been for you at…

Jean Chatzky: (27:26)

I was going to Wisconsin until I got in. That’s where I was going.

Ron Lieber: (27:29)

So was the experience in the classroom really that much better than it would have been at Wisconsin? You know, if I was evaluating that as a parent, I would say probably not $200,000 better and probably not even close. Then the question you have to ask yourself, number two, right, is the kinship. And this is where your own sort of personal snobbery and elitism comes into play. Because the question you have to ask yourself there, one of the most incredible things that somebody said to me was, it’s an Ivy league graduate, a former colleague of mine, came up to me at a speech many years ago and introduced me to his college roommate. College roommate of 55 years ago. They were still best friends. And Steve, he said to me, Ron, he said, at college, I met the sort of people who I never could have imagined existing in the world. So is that $200,000 more likely to happen at Penn than it is at Wisconsin? I have my own feelings about Penn as it exists today, which I’ll keep off the broadcast. But that’s the question that you have to ask. And then, maybe the most important question is about the value of the credential, right? Because there you’re dealing with other people’s snobbery. And depending on the city where you think you might want to live someday. I know you didn’t have a sense of what the career trajectory was going to be for you. But the fact of the matter is that people say in New York City, maybe at the Time Inc. Building, for instance, might’ve been much more likely to look kindly on an Ivy League graduate than they would have at some quote unquote hick from West Virginia, who went to a hick school in the Midwest, right? And I can say this as an alumni of Time Inc., just like you, that that place was filled with snobs.

Jean Chatzky: (29:14)

Yeah, no question. No question.

Ron Lieber: (29:16)

And did it matter that you went to Penn and did you end up on the trajectory that you did because you were given the benefit of the doubt? I think the answer is yes. Could you have done it anyway? Might you have? Sure. But it would have required a lot more aggressiveness and much more work on your part. So whatever, knowing Jean Chatzky, I think you probably would have pulled it off if you were coming from Madison. But we can’t be sure. And this is the thing. We don’t to do both and test them.

Jean Chatzky: (29:42)

Right. For me, the kinship was above and beyond, right? I had a zoom with my college roommate from freshman year and we were not best friends, but we zoomed just this week, which was, as she put it, a nice benefit of the pandemic. I know we’ve got so much we want to get to, and I want to talk to remote learning. But before we leave this question of fear and guilt and snobbery, we got a letter from a listener, Pat, for our mailbag. I actually want to get your take on it because it’s so relevant. She writes, my child is going to college in September. He’s going to take out $5,000 in loans each year, but I’m going to pay $4,000 a month, which is going to be really hard for me. I agreed to this and I feel I need to keep my word. I’m over 65. My job is relatively secure. I thought I would sublet my apartment for two years. I have somewhere else I could live and use that money. But with the pandemic, I’m no longer sure that this is a viable option. Do you have any suggestions? I have about $700,000 in my 401k and no other savings. So, in part, I wish she had heard this episode a year ago, right? But as you said, we can’t rewind the clock. What would you suggest to her?

Ron Lieber: (31:03)

Do we know if this is her only child or her last child?

Jean Chatzky: (31:08)

It kind of sounds like it to me. Because she says my child.

Ron Lieber: (31:11)

Well, I guess the assessment you have to make at that age is, how’s my health? What’s the likelihood that I may not be able to work, even if I’m willing to work? I would do a gut check on the employer’s willingness to have me around. I would imagine for myself what it would mean to not be able to put, you know, if the alternative was $2,000 a month instead of $4,000 a month. What we’re talking about here is an extra hundred thousand dollars in the retirement account. So what is that really going to mean when you hang it up in presumably five years and you have to start drawing that down at roughly 4% a year. How much of a difference is that really going to make to how you live your life and what you can do for your grandkids someday, if you have them, and how much you can see them. You know, ask yourself that granular question. Because I have no particular beef with parents who choose to make the more expensive choice. I just fear that so many people have regrets when they don’t ask hard questions about value at the front end. And at this point, it’s probably too late to consider other options, although plenty of good schools and plenty of reasonably selective schools will actually take applicants months after their stated deadline. And so, if you wanted to pivot, you could. But it sounds like this particular kid may already sort of have their heart set on this, right? So you need to ask the granular questions about what is this really going to mean for my life? And the fact that she’s so close to retirement, she actually has pretty good visibility on what it’ll mean. And so what would she have to give up?

Jean Chatzky: (32:56)

Yeah.

Ron Lieber: (32:56)

And that’s the question that you ask.

Jean Chatzky: (32:58)

And I also think this option to sublet your apartment, reading between the lines a little bit, hopefully we are near the tail end of this pandemic. And it’s a nice option if you do have somewhere else you can live, and you can come up with the money that way, without having to raid your retirement or live in an uncomfortable manner. If you can look six months down the road and sublet then, rather than subletting now, that may be something that you’re comfortable with. I also think any apartment that you can sublet, that is going to spill off this much cash, is probably a pretty valuable apartment. And you may want to look down the road at how you are thinking about accessing the value in that should you ever need it in your retirement.

Ron Lieber: (33:55)

I’m so glad you brought that up because there’s this supposed truism of personal finance in this realm, that’s actually a lie. You know, people are always saying, well, you know, you can’t borrow for retirement, right? So better to borrow for education is sort of the implication. But that’s not true. You can borrow for retirement. You can take a reverse mortgage out. Now there are lots of problems with reverse mortgages, but it just isn’t true that you can’t borrow for retirement. And if she has that asset, you know, maybe that’s something that she can draw on that will allow her to increase her quality of life, albeit while reducing the inheritance that the kid will get some day. So there are options.

Jean Chatzky: (34:37)

Right. There’s life insurance. If you have a life insurance policy with a cash value where the dependent no longer needs it, you can pull on that as well. So I agree with you there. I also think, and I’ve been saying this for a long time. I get the, you can’t borrow for retirement, you can borrow for college. I just don’t think the person who said that first was a parent. I think it doesn’t, you know, parents are not going to do that, right? We’re going to help our children because that’s what we do. And the question is, how much do we help them? How much do we take a step back? How long do we spend in the workforce? As we wrap this up, remote schooling, how has this changed the landscape? Are online courses becoming a realistic way of cutting the price of college.

Ron Lieber: (35:30)

Sure. So in answering that question, we have to remind ourselves what college is, and the fact that different people define it in different ways. Cause here was what was so interesting about what happened starting in March and watching it from a distance. Online college was already a reality and already really good for many kinds of people. All sorts of people who didn’t go to college at the traditional 18 to 22 age, but eventually wanted to go back and get some credits or get their degree. The ability to do that kind of on their own terms, on their own time, via online schooling, already existed and it was great, right? You know, Southern New Hampshire University does it and Arizona State does it. And all sorts of state universities have ways to do it. This stuff is out there and the technology was really good and it was working fine before March, 2020. What we did in March, 2020 was something very different. We took a whole bunch of people who had signed up for what has become a rite of passage for the middle class and above in the United States, which is residential undergraduate education. We took all those people. We pulled the rug out from under them. We sent them home and all that stuff we were talking about before, right? You know, the learning, having your mind grown and mind blown, that was all gone. We just shoved them into zoom rooms with professors who couldn’t even use the technology, and didn’t know anything about online pedagogy, right? So the learning was taken away. The kinship was gone cause your friends are scattered about, right? The only thing that was left was the credential. So no wonder people were mad and no wonder, against all reason and against all public health advice, they came sprinting back to campus in September paying full price or more than they had paid the previous term. And a whole bunch of them got sick and infected a bunch of people in town and probably killed them, right? So what just happened here? Well we did not prove that residential undergraduate higher education is bubble? I think we proved something like the opposite, which is that people really love this stuff, right? They love going to college. They came running back and they weren’t demanding 10 to 20% discounts. You know, a few schools gave a little money back, but for whatever reason, it’s not that I think this industry is recession proof or bubble proof. I mean, it’s certainly subject to recessions, but is it a bubble? Is some freight train of technology coming to run this whole thing over. It only will if everybody in America who would normally go and live in a dorm, between 18 and 22, suddenly decides that they don’t want to do it anymore. And they liked what they were doing in April 2020 better. And the fact of the matter is, nobody did. They hated it.

Jean Chatzky: (38:17)

On that note, we have to leave it. Ron Lieber, the book is “The Price You Pay For College.” Where can we find more about you?

Ron Lieber: (38:26)

So RonLieber.com is where you can find me and say, hello. That’s L I E B as in boy, E R. You can sign up there to get occasional dispatches for me. And I’m on all the usual social media channels, @RonLieber, Twitter and Instagram in particular.

Jean Chatzky: (38:41)

Thank you so much.

Ron Lieber: (38:42)

It was a pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Jean Chatzky: (38:44)

Of course. And we’ll be right back with Kathryn and the rest of your mailbag.

Jean Chatzky: (38:53)

And HerMoney’s Kathryn Tuggle joins me now. What an interesting conversation.

Kathryn Tuggle: (39:00)

That was amazing. I love Ron. I devour everything that he writes. And in preparing the script, I was looking through the book and I found myself thinking every other sentence, oh my God, yes. This is exactly what we need. Oh my gosh, yes. This addresses that question or that question or that concern. He has his finger on the pulse of what is happening right now like nobody else I think who’s writing today.

Jean Chatzky: (39:26)

I agree with you. I also think that it’s very tactical in a helpful way. You know, yes, there is a decent amount of policy in it. But it’s nuts and bolts in a way that I know that our community really needs. I mean, that’s what we get the response from when we publish it on HerMoney. When we get tactical. When we really break down, okay, how do you solve this particular financial issue? How do you deal with this particular financial problem? That’s what people need, right? I mean, we can fluff it up as much as we want, but it’s the tactics in plain English that are missing from most financial education these days. And I think particularly when it comes to this expenditure, this confusing and emotional expenditure. Much, much needed. So I was very happy that he was able to spend so much time with us. That was terrific. And he lightened your load for today cause I stole the mailbag question and threw it at him. So let’s take what we have left.

Kathryn Tuggle: (40:33)

It’s a good thing I don’t do mail bag questions on commission because you’re always like randomly stealing one from me.

Jean Chatzky: (40:41)

It’s nice. I mean, I do it because you set it up, by the way. I mean, you pull the questions and you put them into each episode and you do it for a reason. And sometimes I think, oh my gosh, I have this person in the studio. They are going to be able to give some additional perspective that I’m not going to bring. So yeah, let’s just use their expertise while we’ve got it.

Kathryn Tuggle: (41:04)

Absolutely. All right. Well, our second question of the day is from Ginger. She writes, what’s the best way for my two college-aged daughters to establish Roth IRAs. Do you have recommendations on the steps they should follow or the companies they should use? What should they consider when doing so? Thanks.

Jean Chatzky: (41:23)

Ginger, this could not be easier. I recommend that you do it with a company that has a very, very easy online interface or app. That includes our sponsor, Fidelity. But there are other brokerage firms out there with very, very low costs that fall into the same kind of traditional firm model that I would have you look at. Or you could look at a robo advisor. When my son was opening his Roth for the first time, and he did it coming right out of college, he liked the robo advisor process. The questionnaire that it ran him through to figure out how much risk he wanted to take. And he went with a robo advisor. So, in addition to Fidelity, Vanguard, Schwab, you could look at Betterment. You could look at Wealthfront. You could look at Ellevest. The most important thing to think about is whether your child is making a contribution once, say at the end of a summer of earning money for the year, or will they be making it consistently throughout the year. As they enter the workforce, I like to see them turn on the ability to invest automatically on a monthly basis. Because that money adds up and then they’ll get to have that miraculous moment where the light bulb turns on and they’re like, oh my gosh. Look at what I’ve done. I have all this money. That happened for my son. He actually called me and he said, why didn’t we do this sooner? And that’s what you want. You want them to feel the satisfaction of the fact that they are a) saving successfully, but b) that their money is growing. That it’s working for them. And hopefully the markets cooperate. So it couldn’t be easier. It’s a five minute to 10 minute transaction and sooner is better than later.

Kathryn Tuggle: (43:30)

Absolutely. And it’s so amazing that you’re thinking about this now. Because your college-age daughters probably aren’t, and they are going to be so, so thankful that you did.

Jean Chatzky: (43:40)

Yeah. A hundred percent.

Kathryn Tuggle: (43:42)

Our last question comes to us from Shannon. She writes, hi Jean. I’m a new listener to your podcast and I’d love your advice on what financial steps I should take next. I’m a 28 year old woman and currently earned $43,000 a year. I’ve paid off just over $50,000 in student loans over the past five and a half years. And I have $5,000 left in private student loans at 6% interest and $11,000 left and federal student loans with varying interest rates. Instead of saving for retirement, I targeted paying down my student loans. My current employer does not contribute to retirement. I’m also starting a part-time MBA program, aimiing to complete the program without taking out additional loans. I have a thousand dollars in savings and with the extra payments on my loans, I don’t have much left at the end of the month. My partner and I live together and he has a larger savings in case of emergency. I’m wondering if I should shift my focus towards saving for retirement and paying for grad school, and just start making minimum payments on my loans. Or should I pay off the private student loan before transitioning my focus toward retirement? I don’t have any other debt and would like to add that I do have a very small amount in an old retirement account, about $5,000, from a previous employer. Any advice is appreciated. Thank you so much.

Jean Chatzky: (44:58)

First of all, can I just say, congratulations on making such headway on those student loans at your salary? I don’t know exactly…

Kathryn Tuggle: (45:09)

It’s remarkable.

Jean Chatzky: (45:09)

Yeah. Amazing, right? I mean, I don’t know exactly where you’re living. I don’t know if you lived with your parents for a while. I don’t know how you paid off $50,000 in student loans on a $43,000 salary, which probably started significantly lower, and managed to live your life without going into debt. I know people do it, but you have clearly been both devoted to your goals and very strict with yourself as far as the amount of money that you allowed yourself to spend. I would shift some of your focus toward paying for retirement. I would try to start, and you can split the difference if you want, or you can go ahead, and you can start making minimum payments on those student loans. I would look to get into whatever retirement account you are offered at work and make an automatic contribution that you can afford. As far as graduate school, I do think that the idea of doing it in a way where you’re not accumulating additional debt is amazing. It’s wonderful. If you can accomplish that, I think that’s terrific. But even though you are probably not going to be able to max out your retirement savings, what you want to do now is get in the habit of saving for retirement with each and every paycheck. And though, in another scenario, I would suggest that you try to refi those private student loans, because they’re at 6% interest and you can, if you’ve got a good credit score, which I’m sure you do, you can typically get an interest rate that’s half that large. Often the student loan refinance companies won’t look at you unless you’ve got $10,000 in debt. So just have at it with the monthly payments. It’s time to put these loans to the side and focus on your other adult goals, including getting that MBA, which will boost your salary, which will enable you to supercharge your way to retirement. But really good job. Really, really good job. The last thing is, the thousand dollars in savings is a little bit low. So if you could just maneuver your way to putting a little bit of money, even $25 a month, toward that savings account every single month, I would feel better about that.

Kathryn Tuggle: (47:47)

That’s a great point Jean. And absolutely such a great job paying down those loans.

Jean Chatzky: (47:53)

Amazing. Amazing. A really good example. I wish I knew where she lived, because I’d just love to have some sense of the cost of living there. But such a good example of what we can do when we prioritize. So thank you so much Kathryn.

Kathryn Tuggle: (48:07)

Thank you Jean, as always.

Jean Chatzky: (48:09)

Of course, and in today’s thrive, we’re going to talk about some financial moves to make now, to get your high school senior ready for college next year. If you’ve got a child who’s a senior, you know it is an exciting time for the whole family. In many ways, it is the bridge between childhood and adulthood. But because of that, it’s time to tackle some important money related topics and action items with your child, so that they can get ready for financial independence. At HerMoney.com, we’ve got a rundown on the top five ways to help your child get off to a great start in college. Here are a few of our favorites. First, discuss the financial investment of their college experience. This lines up so nicely with the conversation that we were having with Ron earlier. But take the time to talk over what they can do to make the best of that experience and the magnitude of the funds being spent. Your child needs to understand that the tuition dollars that they and you are spending are an investment in their future. They need to understand the need to live within the budget they have while they’re there, which will mean doing things like cooking or eating on the meal plan, purchasing used textbooks and not skipping class once those tuition dollars are paid. Every skipped class can technically be considered a loss. Also talk to them about minimizing student debt in a way that they can understand. Recent graduates are often overwhelmed by the debt that they accumulated in college, and that debt can be overwhelming. It can reduce the joy of a new career. Just to put it in perspective, a $50,000 loan paid back monthly over 10 years at 6% interest, that’s a $555 monthly payment. That’s huge when you’re living on a starting salary. And it can influence every life decision that you make. And so, if you and your children are actually looking at which college to attend right now, as many families are, these are the sorts of things that you want to take into consideration. With your guidance, there is no reason your child can’t start freshman year off empowered financially, and ready to handle the big decisions that come their way. Thank you so much for joining me today on HerMoney. Thanks to Ron Lieber for the candid conversation and the deep dive into what it really means to invest in an education. I can’t wait for all of you to pick up a copy of his book and learn more. If you like what you hear, I hope you’ll subscribe to our show at Apple podcasts. Leave us a review. We love hearing what you think. We’d also like to thank our sponsor, Fidelity. We record this podcast out of CDM Sound Studios. Our music is provided by Video Helper. And our show comes to you through Megaphone. Thank you so much for joining us and we’ll talk soon.